The EU has implemented just a fraction of the proposals made by former Italian premier Mario Draghi on revitalising the bloc’s flagging economy in the race against global rivals such as China and the US.

Back in September 2024, Draghi set out 383 recommendations warning that Europe faced an “existential challenge” and would “not be able to become a leader in new technologies, a beacon of climate responsibility and an independent player on the world stage” unless it became more productive.

But a year on, despite the European Commission’s pledges to move quickly, only 11.2 per cent of Draghi’s ideas have been implemented, according to an audit by the European Policy Innovation Council, a Brussels-based think-tank.

Meanwhile, Europe’s economy has continued to flatline, with the US economy expanding eight times faster than the EU’s in the second quarter of 2025, according to Eurostat data. EU officials argue that European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who had tasked Draghi to write his report, has been too preoccupied with averting a full-blown trade war with the US, keeping the Trump administration engaged on Ukraine and striking the right balance with China.

National leaders in Europe have also been reluctant to set aside their countries’ sensitivities and embrace more of the former European Central Bank president’s proposals.

The competitiveness agenda seems blocked, said one EU diplomat. “The commission is trying, but ultimately it depends on national leaders. Meanwhile, we are losing time.”

Most of the progress made has been in areas of least resistance, such as joint borrowing for defence, or slashing red tape, according to Deutsche Bank analysts. “So far we would not describe as game changers any of the proposals that they have done,” said Marion Mühlberger, senior economist at Deutsche Bank.

A commission spokesperson defended the commission’s record, saying it had “acted quickly to implement [Draghi’s] key recommendations”, noting support for AI gigafactories, cleantech manufacturing and strategies to grow private capital investment.

In her annual address to the European parliament on Wednesday, von der Leyen highlighted the bloc’s measures to ensure Europe becomes more competitive, as “Europe’s independence will depend on its ability to compete in today’s turbulent times”. She will also present a road map to 2028 to ensure “clear political deadlines” to complete the single market, especially on finance, energy and telecommunications.

European Policy Innovation Council scoreboard

| Category | % of total | Number of measures |

|---|---|---|

| Implemented | 11.2% | 43 |

| Partially implemented | 20.1% | 77 |

| In progress | 46.0% | 176 |

| Not implemented | 22.7% | 87 |

| Total | 100% | 383 |

But outstanding projects remain elusive, such as the establishment of a capital markets union, eliminating barriers in the single market and harmonising more rules that drive up the cost of business.

Stéphane Séjourné, the EU’s industry commissioner, blamed member states for the lack of progress, particularly on the EU’s single market. One EU law should replace 27 national laws, making it easier for businesses to operate in the bloc, he said. “We say that, on paper, everyone is in agreement,” he told lawmakers last week. But when the decision reaches EU governments “there is opposition”.

Governments are protective of their national rules, said Oscar Guinea of the European Centre for International Political Economy, who argues for more harmonisation in the services sector, as Draghi recommended.

The “lack of a single market for services stops the adoption of digital technology and the appearance of digital companies”, he said. National leaders in October will discuss competitiveness, said António Costa, the EU Council president who is chairing the meeting.

He told the Financial Times that the summit will be “a very important moment” to push for a capital markets union, the digital euro and how to strengthen the international role of the single currency. In January, Brussels published a Competitiveness Compass, which distilled Draghi’s principles into priority areas such as joint purchases of critical raw materials and reviewing capital requirements to free up bank investments.

But the commission has shied away from pressing for the most radical of Draghi’s demands such as joint funding for key strategic industries and common infrastructure. Its major focus has been on “simplification and deregulation”, said Bas Eickhout, co-leader of the Greens in the EU parliament.

“This commission has not done enough on competitiveness because they have chosen a very narrow definition of competitiveness, which I don’t think is the biggest problem of Europe. Yes we are bureaucratic but lack of investment is Europe’s biggest problem.”

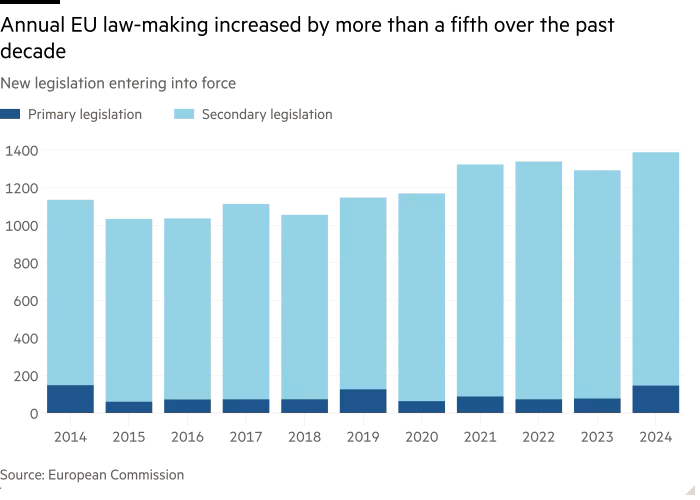

In von der Leyen’s first term, the commission increased legislative output by 17 per cent compared with her predecessor, according to FT analysis. The rise was mostly driven by an increase in secondary legislation — detailed rules that descend into technical detail over the application of EU laws.

But von der Leyen’s second-term efforts to cut red tape, as recommended by Draghi, has in some cases created more uncertainty for industry — packaging various pieces of legislation in “omnibus bills” and replacing complex regulations with simplified versions that are often scant on detail.

For Sander Tordoir, chief economist at the Centre for European Reform, simplification is a sideshow rather than the main medication. “You can have a bonfire of regulations and if you have none of the other policies Draghi recommended . . . nothing is going to happen.”